Hey Everyone,

I believe in transparency, so here’s the deal: Last week was Fall Break for my kids, and I didn’t get anything done.

Why? Because we went to The Most Magical Place on Earth™️. It was terrific, exhausting, and taxing in all the best ways.

But it wasn’t productive. Pulling together a coherent thought was next to impossible at the end of the day. So this week, I’m publishing an older post I wrote about the financial consequences of hiring. It fits in well with my other posts regarding Why you should care about your hiring process. I’ve been saving it for just such an occasion, so I’m glad the timing worked out.

I hope it helps, and, as always, thank you for reading!

Ben

💸 It's Going To Cost You 💸

A reluctant look at the price we pay for average hires

A mentor recently said to me, “Your idea to fix the hiring process is great, good for you. But for anyone to care, you have to present a compelling financial case.”

This mentor is incredibly experienced, patient, and helpful. He’s also right.

The goal with this post is to make a case that slight differences in who you hire can cause significant and compounding financial impacts to your business, encourage you to define what good and bad means to you, and help you determine if changing your hiring process is worth it.

After all, changing your hiring process is hard work. Really hard. And, as much as I (we?) like to think altruism will rule the day, there has to be a meaningful financial return on investment if we’re going to dedicate the time and energy required to think critically about how we evaluate talent.

Why I’ve never done a bad hire calculation

Determining how much a hire is worth to us, in pure dollars and cents, is the first step in deciding if the time investment is worth it.

There are several reasons why I’ve never built a financial model to determine how much a bad hire has cost my organization or me:

Reflection hurts - I haven’t always thought critically about my hiring decisions, and I’ve made some pretty egregious mistakes. Thinking about those mistakes isn’t fun.

Virtue Signaling is good enough - I get to virtue signal and say things like “Structured interviews are twice as likely to predict candidate success compared to unstructured interviews.” It makes me feel smart!

“Charlatan” association risk - You’ve doubtlessly seen the recruiters and “people consultant” types who make claims using dubious evidence to scare employers into using their services - things like “Each bad hire costs an organization $1,000,000!!!” Their claims are thin on real data, superficial, 100% fear-mongering, and clickbaity. Who wants to join that chorus?

But my reluctance does not make my mentor’s challenge any less valid. Despite my displeasure, I (and, by extension, we) need to get used to the idea of defining and quantifying what a bad hire means to us. We may believe that we want to implement more fair and equitable hiring practices just because we’re good people. That’s great - but ignoring the financial costs excludes a powerful motivator to change our and others’ behavior. After all, money talks.

So here we are, time to put on my capitalist hat. And, to ensure that I understand the nuance of the situation and make this credible, I’ll use my own experience in sales.

Introducing 80% & 100% Me: The Year 1 cost of a “Pretty Good” sales hire

One of my first big jobs was in sales.1

Newly married and fresh out of grad school, I got a job as an Outside Account Executive at a software company. I found myself on a 50/50 plan (half my compensation was base salary, the other half was “variable comp”) with On Target Earnings (“OTE”) of $120,000. My quota was $1,000,000 annually, meaning that every quarter I had to sell $250,000 of our product and services to hit my total payout and make my OTE. So, if I hit my quota on the nose every quarter, I’d earn $120,000 a year. Sales comp plans can get pretty complex, but the one I was on is relatively common.

Thanks to my youthful naivete, unintentionally great timing, luck, and the motivating presence of student loan debt, I managed to do well despite my inexperience. I averaged well over 100% quota attainment throughout my tenure, and according to the Redpoint 2020 GTM Survey, I was incredibly fortunate to be a top performer amongst all start-ups. But what if I hadn’t been?

From my own experience as a sales manager, I know that 70%-85% of attainment is far more common than 100%+. Redpoint’s data backs that up; the most common level of team attainment was 65%-80%, and fewer than 15% of respondents had teams that achieved 95%+ of quota. Think about that: 85% of sales teams achieve less than 95% of quota.2 That means that there are lots and lots of reps who are just OK in terms of quota attainment. What if I had been “just OK” and averaged 80% attainment?

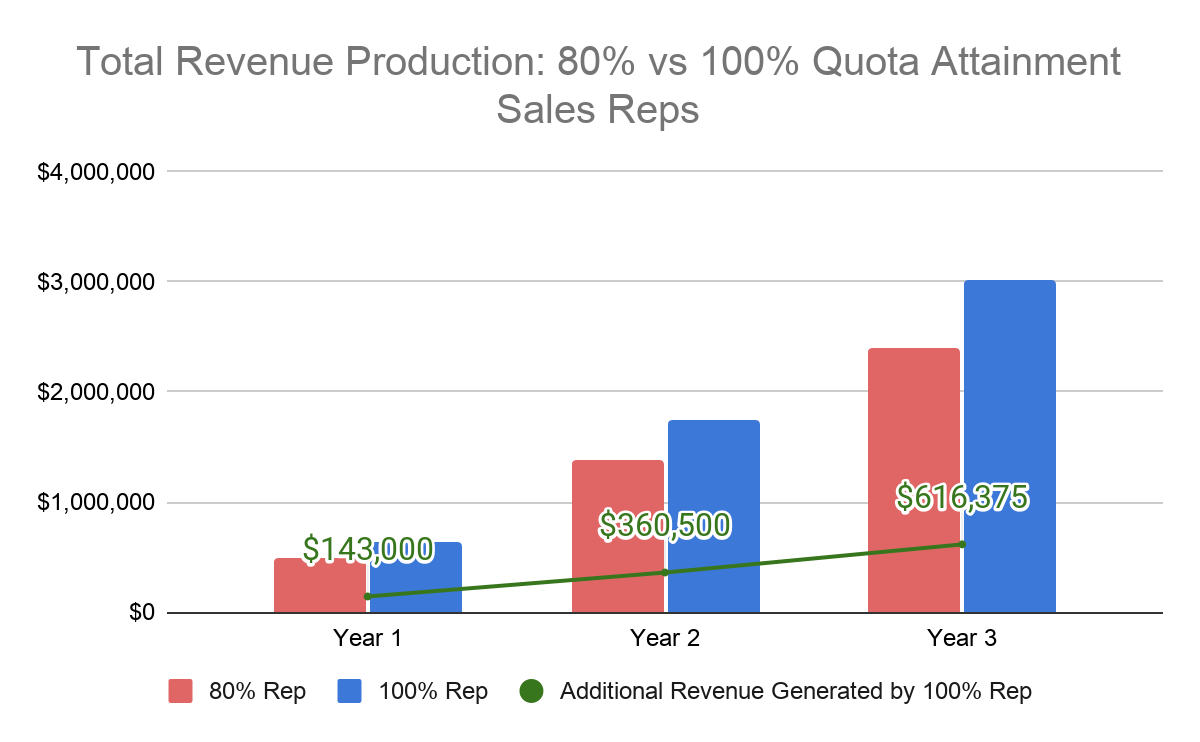

I did that math. Assuming an Annual Contract Value of $50,000, 100% Me would have eleven more customers and generate $143,000 more revenue in their first year than 80% Me. That’s significant. 100% Me would generate enough extra income to hire another rep (and that’s including a five-month ramp period) in my first year alone. Again, 80% Me is just OK, but far from getting fired. They’d probably be a respected member of their team. We’ve all hired someone or had teammates who couldn’t get it together, and those people are going to get let go (and be expensive), but that 80% Rep? They’re going to stick around and everyone will be thankful to have them.

The compounding power of customer retention - Or how mediocre hires get more costly

Now, let’s assume that you, like me back in the day, are in a business that pursues recurring revenue. Sales Reps are paid out on new business, so you have another Existing Business team that will take over an account. Their job is to grow the value of that recurring revenue.

Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) companies measure recurring revenue growth with a metric called Net Revenue Retention (NRR). NRR is calculated by comparing how much revenue a cohort of customers generates from one time period versus another. According to Jamin Ball’s Clouded Judgement, the current median NRR for a publicly traded Cloud / SaaS company is 115%, which means that a customer worth $100,000 this year will likely be worth $115,000 next year.

You see where I’m going with this. The extra revenue starts to compound pretty quickly. Let’s check in on our 100% and 80% Reps after three years.

Yep, that’s right. 100% Rep has generated an additional $616,375 in revenue in just three years. And that’s after salary and bonuses are paid out.

If you’re like me, the rabbit holes are starting to open up. As I write this (Q2 2021), valuations of 25x revenue for growth stage start-ups are far from crazy - so for every $100,000 of revenue you could be adding $2.5M to your company valuation. This effect is significant if you’re a start-up in fundraising mode and looking to avoid dilution. Unsurprisingly, compounding revenue paints a less appealing picture for an underperforming (and even average) sales rep.

What to do about it

Determining the cost of a bad, OK, or great hire is not rocket science, but you do need to know your business and crystalize your expectations. In a practical sense, this means that you:

Establish objective measures of success - “How can we measure good/bad objectively?” Admittedly this is a relatively straightforward process for sales positions, but it can be difficult for others.

Understand your opportunity costs across multiple periods - “What is the immediate cost of a bad hire? What are the long-term implications? What should we optimize for?”

Benchmark against industry and function - “What do other companies like us do? What’s comparable in terms of performance?” Consider these questions a sanity check. Do you expect your four-person finance team to perform and a similarly sized competitor with eight employees? If so, what makes you unique?

Be honest about your investment in your employees - This is a tough one, so be honest with yourself. “Do we have the time to invest in training and developing an employee? If they’re bad or just OK, do we have the ability and desire to get them up to speed?” If you, or your organization, can’t afford to train and develop, that’s OK - but you’ve got to get high performers right out of the gate and be willing to fire fast.

Final thoughts

One of the first steps in fixing your hiring process is determining if investing the time in improving it is worth it.

Be wary of anyone who tells you your bad hires are expensive. Of course, they are. They are also a huge pain, a time suck, and demoralizing for you and your team. But those “experts” cannot understand your situation, core business, and, most importantly, your money. That’s on you.

Sit down to determine what’s good, what’s bad, and the cost of adverse outcomes. You know your industry, company, business, and people well enough to decide what will and won’t work. Most importantly, you owe it to your organization, yourself, and your sanity to define the financial impacts of your hiring decisions.

And once you have that business case done, it’s time to do the actual work on improving your hiring process: determine the traits and skills you need for the role, evaluate candidates objectively for those attributes, and iterate as you learn.

A quick caveat: I’ll be using my own sales experience as the basis for comparison. I realize that there are millions of sales compensation plans out there, each with its details. Will I leave out subtleties like bonus accelerators, spiffs, variances in day-to-day performance, and other aspects of the job that make sales roles financially rewarding and fun? Yes. The aim is to provide an evidence-based example of what a good vs. OK hire looks like, not perfectly simulate reality.

I know that teams are not individuals and that most sales leaders shoot for 85% attainment - again, trying to simplify here.